On April 29, 2017 at 6:12 p.m., Anne died.

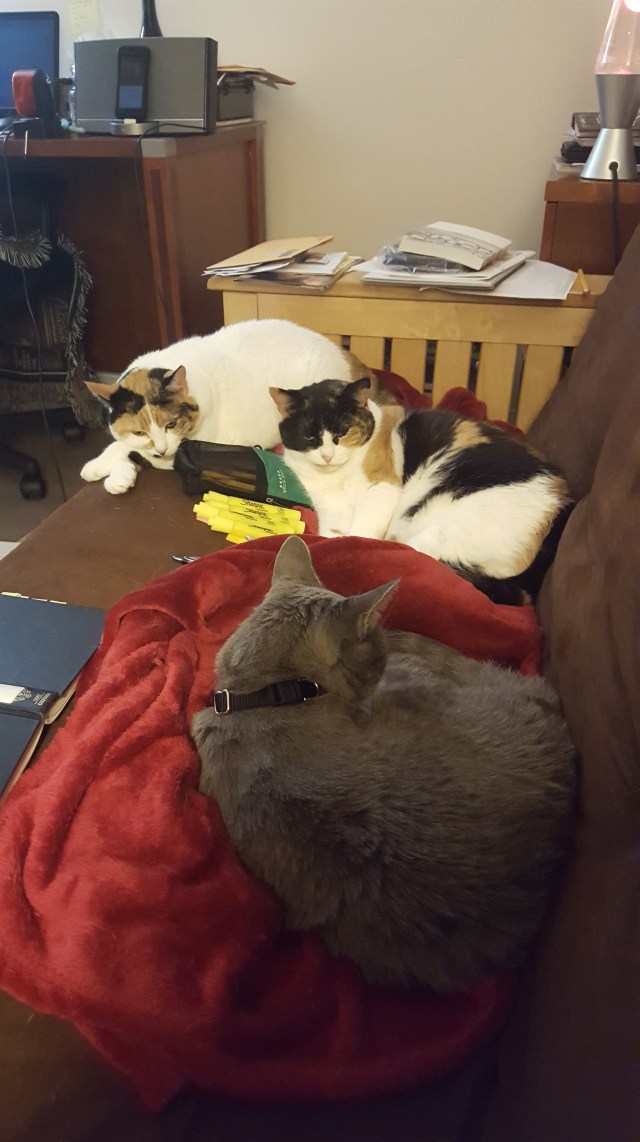

Today, the fall of 2003 feels like a distant memory. I was working at Plimoth Plantation in my first year as a historical interpreter (read: professional pilgrim), and my mother called me to tell me about a litter of kittens the curator of a different museum had  found in a rather remote part of Rhode Island. At the time, I had a cat–Harriet–but she had some significant health problems and appeared to be quite a bit older than the shelter from which I had adopted her originally believed. I wasn’t convinced I was even interested in visiting them, let alone considering adoption. Then, she showed me the curator’s email message, complete with desperate plea and adorable pictures of three kittens, all females. That was it–I committed to adopting all three, and, I immediately started working on identifying a proper “trio” of names for them. In the end, as a group, they became known as the “Bronte sisters”: Charlotte (grey tiger); Emily (mostly white calico, in the center of the picture above); and Anne (more colored calico, in the back).

found in a rather remote part of Rhode Island. At the time, I had a cat–Harriet–but she had some significant health problems and appeared to be quite a bit older than the shelter from which I had adopted her originally believed. I wasn’t convinced I was even interested in visiting them, let alone considering adoption. Then, she showed me the curator’s email message, complete with desperate plea and adorable pictures of three kittens, all females. That was it–I committed to adopting all three, and, I immediately started working on identifying a proper “trio” of names for them. In the end, as a group, they became known as the “Bronte sisters”: Charlotte (grey tiger); Emily (mostly white calico, in the center of the picture above); and Anne (more colored calico, in the back).

Although I had lived in multi-cat households in the past, I failed to realize that, when several cats are involved, essential roles are distributed among the inhabitants largely based on personality. While Charlotte was the “alpha” cat and Emily more easy going, Anne was far more complex.  Anne grew into a larger cat than Charlotte, and there was an unspoken “understanding” that she could, if pushed, wrestle her to the ground, shattering the “alpha cat” illusion irreparably. But, Anne rarely challenged Charlotte’s dominance. On only a few occasions, Charlotte, for one reason or another, went a step too far, as far as Anne was concerned. I remember, several years ago when I was living in New Hampshire, observing Charlotte make a fatal mistake–batting Anne in the face when she was on her way to the food dish. Anne’s eyes immediately narrowed, she stared fixedly at her sister, and she chased her directly under the bed in the room down the hallway. To add insult to injury, she sat just beyond the perimeter of the bed, occasionally peering under it to ensure that Charlotte realized she could not physically leave until Anne condescended to allow her to. Anne had a strong personality with which one meddled at her own peril.

Anne grew into a larger cat than Charlotte, and there was an unspoken “understanding” that she could, if pushed, wrestle her to the ground, shattering the “alpha cat” illusion irreparably. But, Anne rarely challenged Charlotte’s dominance. On only a few occasions, Charlotte, for one reason or another, went a step too far, as far as Anne was concerned. I remember, several years ago when I was living in New Hampshire, observing Charlotte make a fatal mistake–batting Anne in the face when she was on her way to the food dish. Anne’s eyes immediately narrowed, she stared fixedly at her sister, and she chased her directly under the bed in the room down the hallway. To add insult to injury, she sat just beyond the perimeter of the bed, occasionally peering under it to ensure that Charlotte realized she could not physically leave until Anne condescended to allow her to. Anne had a strong personality with which one meddled at her own peril.

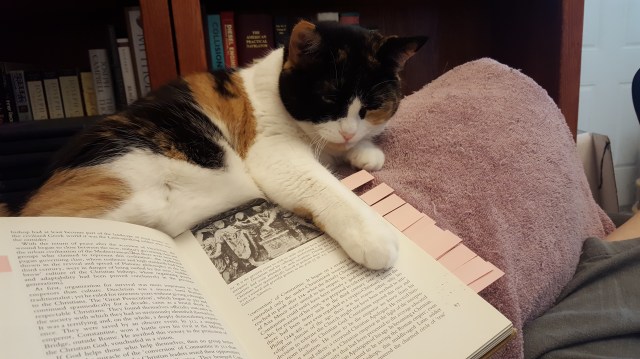

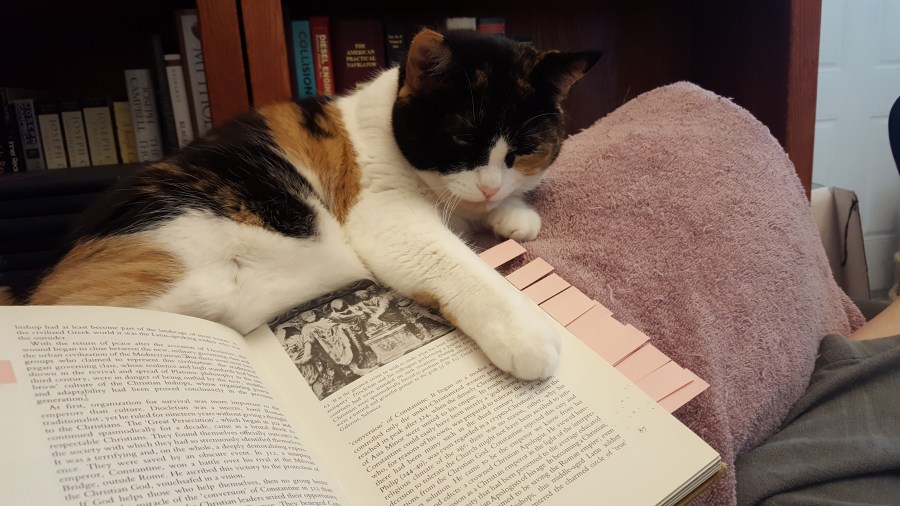

When I moved to Florida to start my PhD at the University of Miami, my relationship with Anne grew particularly close. As I sat and read, studied, and wrote in various places in the house–my office, the green chair in the living room, the couch–she was my constant companion. She quickly figured out my routine, and she started sitting, in the morning, in the room she believed I was most likely to start working in that day. I couldn’t go anywhere without her invaluable “help.” And, she was always a comforting, reassuring presence at particularly high-stress moments. She never left my side, for example, when I was studying for my comprehensive exams or writing my research papers. She was such an integral part of my life–I couldn’t imagine being without her. But, I did at times. Inevitably, I wondered what would happen if Anne was no longer with me; I just hoped that would remain a distant prospect.

When I moved to Florida to start my PhD at the University of Miami, my relationship with Anne grew particularly close. As I sat and read, studied, and wrote in various places in the house–my office, the green chair in the living room, the couch–she was my constant companion. She quickly figured out my routine, and she started sitting, in the morning, in the room she believed I was most likely to start working in that day. I couldn’t go anywhere without her invaluable “help.” And, she was always a comforting, reassuring presence at particularly high-stress moments. She never left my side, for example, when I was studying for my comprehensive exams or writing my research papers. She was such an integral part of my life–I couldn’t imagine being without her. But, I did at times. Inevitably, I wondered what would happen if Anne was no longer with me; I just hoped that would remain a distant prospect.

Unlike my other cats, Anne generally was very healthy for most of her life. Emily suffered from colitis on and off, and Charlotte, most shockingly, developed a benign brain tumor which nearly ended her life. I honestly thought that, based on a  combination of the assessment of her health history and my own personal wishful thinking, that Anne would be with me well into her teen years. One day, I found her sitting in a box by the front door, looking at me sideways out of the lids of her eyes. Now, Anne loved boxes, so I didn’t think very much of it at first. But, then, one morning, she didn’t get out of the box to eat breakfast, and Anne was a very precise, scheduled cat. I realized this while I was on the phone with Stephen, my partner, who was days away from coming home from overseas. I have a distinct recollection of two directly opposed inclinations at the time. While I told Stephen that it was probably nothing; it might be allergies or a fever, and it would be best to get her over to the vet as soon as possible just to be on the safe side, I was thinking–begging the powers that be–that this not be the beginning of what I call the “nose dive.” Some cats, in my experience, have been healthy and active for years only to, quite suddenly, fall irreparably ill and die in what felt like the blink of an eye. I hoped, as hard as I could, that this was not the fate which awaited Anne.

combination of the assessment of her health history and my own personal wishful thinking, that Anne would be with me well into her teen years. One day, I found her sitting in a box by the front door, looking at me sideways out of the lids of her eyes. Now, Anne loved boxes, so I didn’t think very much of it at first. But, then, one morning, she didn’t get out of the box to eat breakfast, and Anne was a very precise, scheduled cat. I realized this while I was on the phone with Stephen, my partner, who was days away from coming home from overseas. I have a distinct recollection of two directly opposed inclinations at the time. While I told Stephen that it was probably nothing; it might be allergies or a fever, and it would be best to get her over to the vet as soon as possible just to be on the safe side, I was thinking–begging the powers that be–that this not be the beginning of what I call the “nose dive.” Some cats, in my experience, have been healthy and active for years only to, quite suddenly, fall irreparably ill and die in what felt like the blink of an eye. I hoped, as hard as I could, that this was not the fate which awaited Anne.

Anne’s case was difficult and unusual from the start, and, in the end, this made a correct diagnosis more of a guess than a confirmed certainty. After a series of complex tests and some experimental treatment, it became clear that we were likely dealing with some form of cancer and the prognosis was far from promising. The primary issue was the fact that, despite multiple tests, we could not confirm, beyond a doubt, what kind of cancer we were dealing with. In the meantime, Anne started to lose weight, but she was largely still fairly robust for about a month or so. In the end, we were presented with a choice: either we could pursue exploratory surgery for Anne to figure out exactly what was wrong, or we could accept the “inevitable” and let her slowly pass away. Still convinced we could possibly save her, we decided upon the former option.

I’ll never forget taking her in to the surgeon’s office for a consultation in about mid-April of last year–I can distinctly recall exactly what I was wearing, what the room looked like,  and every word of our discussion with the surgeon. She explained exactly what she would do, what the goals of the surgery were, but then, she told me something which struck me to the core: if, in her opinion, Anne’s case was particularly bleak and this was apparent during the surgery, she would recommend ending her life on the table. On the surface, of course, this was a practical point–it is notoriously challenging to determine exactly how much discomfort, for example, any sick cat actually is in. But, Anne hated to be anywhere other than home, and the last thing I wanted for her was that her last moments of consciousness to be peppered with apprehension, being in a strange place with strange people. I knew that I had to make sure, as far as I was able, that Anne not undergo the surgery if there was any indication that the surgeon would ultimately be forced to make this call.

and every word of our discussion with the surgeon. She explained exactly what she would do, what the goals of the surgery were, but then, she told me something which struck me to the core: if, in her opinion, Anne’s case was particularly bleak and this was apparent during the surgery, she would recommend ending her life on the table. On the surface, of course, this was a practical point–it is notoriously challenging to determine exactly how much discomfort, for example, any sick cat actually is in. But, Anne hated to be anywhere other than home, and the last thing I wanted for her was that her last moments of consciousness to be peppered with apprehension, being in a strange place with strange people. I knew that I had to make sure, as far as I was able, that Anne not undergo the surgery if there was any indication that the surgeon would ultimately be forced to make this call.

The surgery was scheduled for about five days later. Stephen, always the early riser, always got up before I did, and, each morning, I hoped, somehow, he would leave the room, check on Anne–our first activity every day–and tell me she had passed peacefully on her own. After two nights, I stopped sleeping in the bedroom; instead, I flattened out the futon in my office and slept there with Anne. Sometimes, she slept next to me in the bed. Other times, we “compromised” and she slept in the closet in a box–Anne was, like all sick cats, inclined to hide, but I had to be able to see her and reach her if an emergency situation arose, so I set up the closet in such a way so she would feel “hidden.” I didn’t sleep at all the night before her surgery. We had to bring her to the vet’s office very early in the morning for the procedure, and, when the time came, Stephen asked me if I wanted to come drop her off. I refused; Stephen took her. I don’t know why. I’ve condemned myself for that decision ever since.

Stephen returned about an hour and a half later, and both of us took a nap in the  bedroom. Then, the phone rang–I saw the number, and I thought I knew what was coming. I had to answer it; I took a deep breath and tried to sound composed. She couldn’t go through with the surgery because Anne had become, over the course of the last month, anemic, and it wouldn’t be safe. I breathed again. I asked her what she would recommend–a blood transfusion, and, if this was successful, she would be willing to pursue the surgery tomorrow. I stopped for a minute, and then, I told her: “Don’t go through with it. I don’t think we can save her.”

bedroom. Then, the phone rang–I saw the number, and I thought I knew what was coming. I had to answer it; I took a deep breath and tried to sound composed. She couldn’t go through with the surgery because Anne had become, over the course of the last month, anemic, and it wouldn’t be safe. I breathed again. I asked her what she would recommend–a blood transfusion, and, if this was successful, she would be willing to pursue the surgery tomorrow. I stopped for a minute, and then, I told her: “Don’t go through with it. I don’t think we can save her.”

The surgeon was very understanding, and this decision appeared to have put her more at ease; she must have known what she was likely to find if she did the surgery at that point. She told me something which, over the course of the last year, has continued to give me some comfort in the wake of Anne’s subsequent passing: “You didn’t fail this cat. Science failed this cat. What we don’t know failed this cat.”

Later that day, Stephen and I picked her up from the vet’s office, and it was clear, then, to us, that the only thing we could do was make her as comfortable as possible for however much time she had left with us. Every day was a combination of hopeful moments and signs of the inevitable. She largely spent her time in a cardboard box Stephen had arranged for her, and I would move this box, with her in it, around the house and onto the porch so she was always with me while also being in some of her favorite places. Our vet was very good about providing her with whatever medicines she needed, and, once we gave these to her at the start of the day, she was fine, even content. On Saturday, however, things took a frightening turn.

Stephen went to work that day, leaving me alone with Anne at home. I was teaching an online course at the time, so I set myself up to work in the office sitting on the futon with Anne. At first, after medications, she was fine, but, quite suddenly, she lost her ability to move her back legs and tail. I have absolutely no idea what happened to cause this; realizing this partial paralysis, Anne began flailing around in distress, trying desperately to move. She was in her box, so I moved this onto the floor. Before I could call the vet for help, something happened, and I don’t know what it was–she was moving around and then, quite suddenly, she leaned back in her box and began to cry in distinct physical distress. I called Stephen home, and I told him that he had to call our vet and tell him that it was clear, to me, that the best thing to do was to end her life and suffering as humanely as possible.

Stephen rushed home, calling the vet on the way. He found me in the office, Anne in her box again on the futon, but now lying down making minimal movements and periodically crying out in distress. I had her favorite music on, I talked to her, I reassured her, I held her paw. Stephen sat on the other side of her and did the same. I remember thinking–this is it; these are the last moments I will have with her. I wanted to enjoy them; I wanted to burn them into my memory. But, this wasn’t the Anne I knew for so long. My companion was frightened and a shadow of her former self, and I didn’t want my dominant memory of her, after all she had contributed to my life, to be her pain at the end. When the vet finally came, he examined her and concluded that something had ruptured and there was no other way to help her. I was with her, in her box on my coffee table in the living room, when her life ended. The vet walked out of the room to give us a minute, but what was left was the body that had betrayed her; not the spirit which had kept her vibrant, active, and strong.

It took me a long time to recover from the initial stage of grief after she died. That night, after her death, as I was just about to go to bed, I suddenly heard her crying in distress again, thundering like a clap, over and over again, in my head. I was compelled, the next day, to clean the office and set it up as it had looked before Anne’s illness necessitated a change. I threw out all of the leftovers from the meals I had eaten the day she died. I refused to listen to the songs I associated with Anne, and, one day, months later, when I was visiting the United Kingdom on a two-week vacation, one of these songs came on in a random shuffle on my iPod. I forced myself to listen to it, and then, crying, deleted it from my library. I used to walk at night and look up at the moon, either waxing or waning, struck by how much the combination of dark and light reminded me of her dilated pupils. The cat population–a family of 4 now–also went into mourning. The day after her death, every cat simply sat in the living room, head down, unresponsive to everything from toys to treats. They knew.

Every day, before I go to sleep, I think of Anne–I recall the sound of her voice, her purring, and how her fur felt to the touch on her head, on her back, on her tummy. At one point, I realized that I had a near-perfect memory of everything that happened leading up to her death, and this memory was slowly eating away at all of the others–all of the companionate moments, her quiet presence and her remarkable inner strength. I never want to forget the mundane, day to day experience of Anne in my life; she gave me her trust and her love effortlessly, and, now, I had to make the effort to ensure that this was the Anne I recalled first, before the images of her last days haunted it out of existence.

This is the last picture I have of the three sisters (willingly) together. Of course, when I took this shot, like so many others over the years, it never occurred to me that it would have that distinction, or any distinction at all. It, like so many other things, took on a completely different meaning after Anne’s death last year. I still don’t listen to certain songs I know she liked. I got an e-mail from her cancer specialist’s office by accident today, and, for a moment, I teared up again. I periodically drive in the neighborhood in which the surgeon’s office is situated, and I always avoid passing it directly by. I never again wore the outfit I had on the day I brought Anne to that office and learned what could have been, but fortunately wasn’t, her fate. I realize now that, even if we had a diagnosis at the moment she began to show symptoms, even then, it might have been too late to save her.

I realize now that I’ll never stop missing her. But I know I’ll never forget the best of her, even if I’m forced to remember the moments which were, and always will be, the worst.

Beautifully written. Thank you

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing Annie’s story. I have experienced the same kind of story with the passing of several cats over the years. It is never easy.

LikeLike